The rapid transformation of farming and food systems to cope with a warmer world, such as adopting climate-smart practices, particularly to curb greenhouse gas emissions, is critical for hunger and poverty reduction, the United Nations agriculture agency said today in a new report.

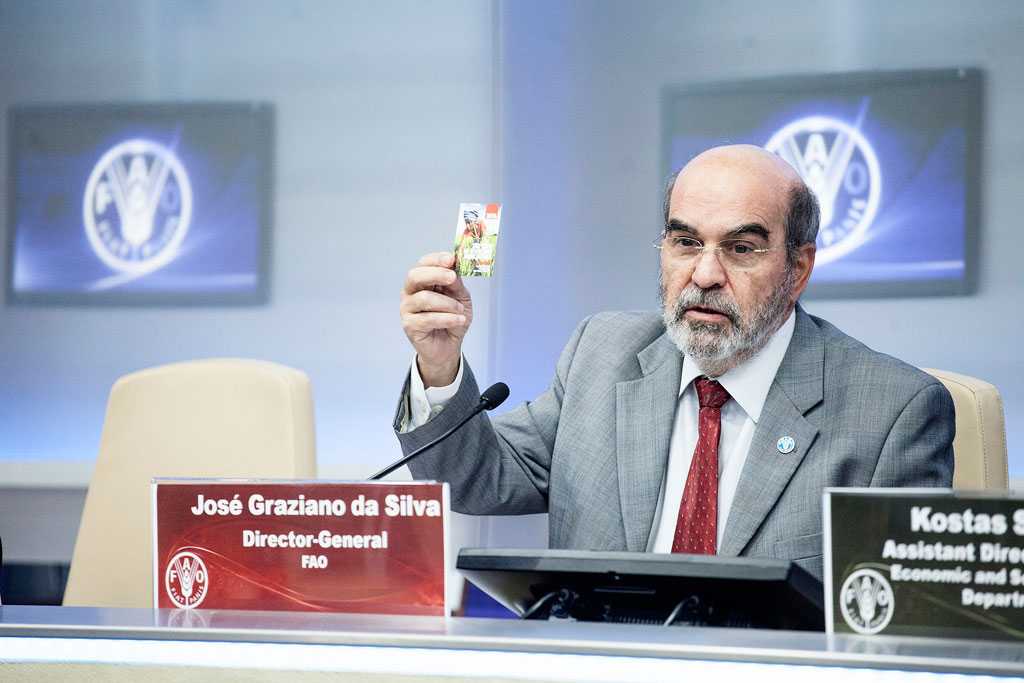

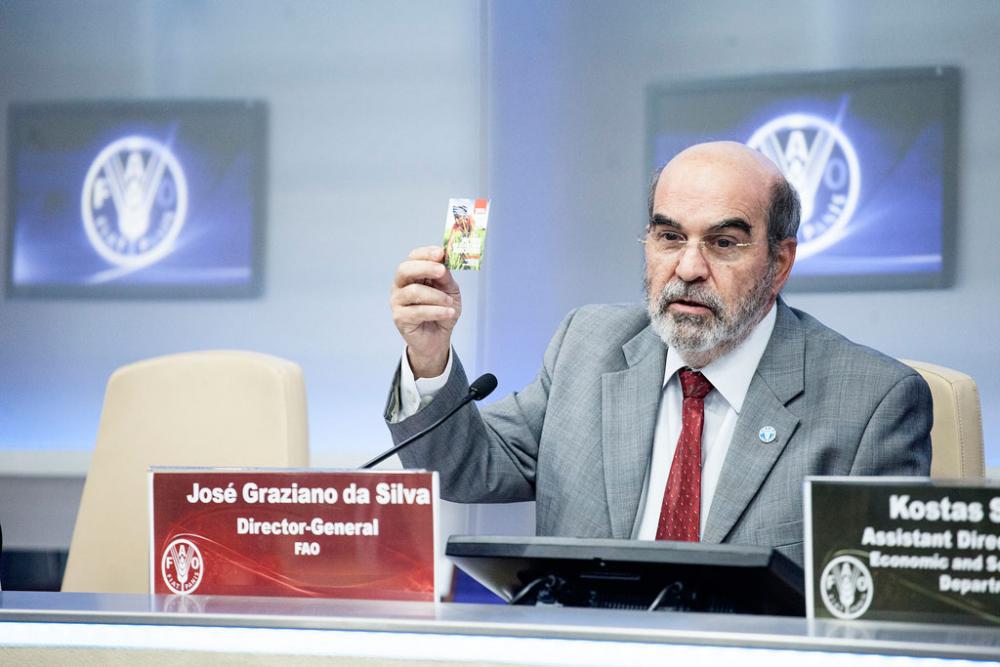

“There is no doubt climate change affects food security,” said the Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), José Graziano da Silva, as he presented The State of Food and Agriculture 2016 report at the agency’s headquarters in Rome.

“What climate change does is to bring back uncertainties from the time we were all hunter gatherers. We cannot assure any more that we will have the harvest we have planted,” headded.

That uncertainty also translates into volatile food prices, he noted. “Everybody is paying for that, not only those suffering from droughts,” Mr. Graziano da Silva said.

FAO warns that a ‘business as usual’ approach could put millions more people at risk of hunger, than in a future without climate change. Most affected would be populations in poor areas in sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia, especially those who rely on agriculture for their livelihoods. Future food security in many countries will worsen if no action is taken today.

“The benefits of adaptation outweigh the costs of inaction by very wide margins,” emphasized Mr. Graziano da Silva.

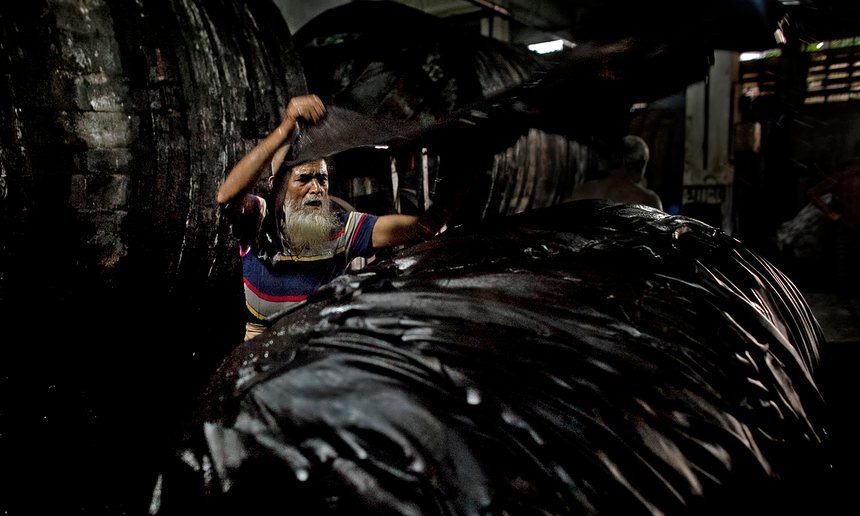

However, it is agriculture, including forestry, fisheries and livestock production, which is contributing to a warmer world by generating around a fifth of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, agriculture must both contribute more to combating climate change while bracing to overcome its impacts, the report says.

Time for action

Without action, agriculture will continue to be a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions. But by adopting climate-smart practices and increasing the capacity of soils and forests to sequester carbon, emissions can be reduced while stepping up food production to feed the world’s growing population, the report says.

The report provides evidence that adoption of climate-smart practices, such as the use of nitrogen-efficient and heat-tolerant crop varieties, zero-tillage and integrated soil fertility management would boost productivity and farmers’ incomes. Widespread adoption of nitrogen-efficient practices alone would reduce the number of people at risk of undernourishment by more than 100 million, the report estimates.

It also identifies avenues to lower emission intensity from agriculture. Water-conserving alternatives to the flooding of rice paddies can slash methane emissions by 45 per cent, while emissions from the livestock sector can be reduced by up to 41 per cent through the adoption of more efficient practices.

“2016 should be about putting commitments into action,” urged Mr. Graziano da Silva, noting the international community last year agreed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement on climate change, which is expect to come into force early next month. Agriculture will be high on the agenda at the 22nd Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), known by the shorthand COP 22, in Morocco starting on 7 November.

Helping small farmers adapt to climate change risks is critical

Developing countries are home to around half a billion small farm families who produce food and other agricultural products in greatly varying agro-ecological and socio-economic conditions. Solutions have to be tailored to those conditions; there is no one-size-fits-all fix.

Helping smallholders adapt to climate change risks is critical for global poverty reduction and food security. Close attention should be paid to removing obstacles they may face and fostering an enabling environment for individual, joint and collective action, according to the report.

FAO urges policy makers to identify and remove such barriers. These obstacles can include input subsidies that promote unsustainable farming practices, poorly aligned incentives and inadequate access to markets, credit, extension services and social protection programmes, and often disadvantage women, who make up to 43 per cent of the agricultural labour force.

The report stresses that more climate finance is needed to fund developing countries’ actions on climate change. International public finance for climate change adaptation and mitigation is growing and, while still relatively small, can act as a catalyst to leverage larger flows of public and private investments. More climate finance needs to flow to sustainable agriculture, fisheries and forestry to fund the large-scale transformation and the development of climate-smart food production systems.