The rapid transformation of farming and food systems to cope with a warmer world, such as adopting climate-smart practices, particularly to curb greenhouse gas emissions, is critical for hunger and poverty reduction, the United Nations agriculture agency said today in a new report.

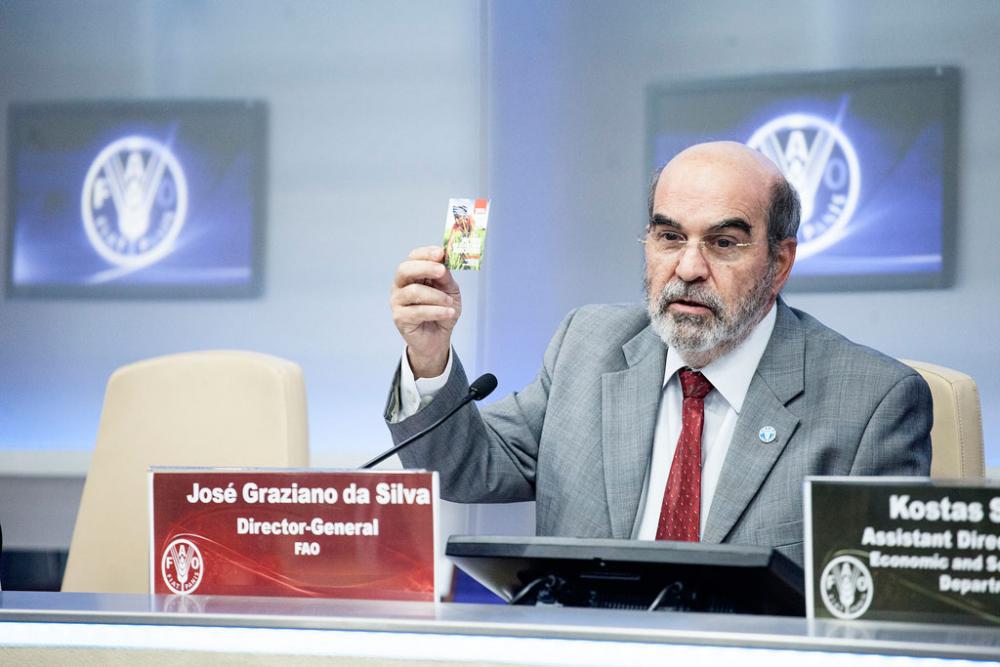

“There is no doubt climate change affects food security,” said the Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), José Graziano da Silva, as he presented The State of Food and Agriculture 2016 report at the agency’s headquarters in Rome.

“What climate change does is to bring back uncertainties from the time we were all hunter gatherers. We cannot assure any more that we will have the harvest we have planted,” headded.

That uncertainty also translates into volatile food prices, he noted. “Everybody is paying for that, not only those suffering from droughts,” Mr. Graziano da Silva said.

FAO warns that a ‘business as usual’ approach could put millions more people at risk of hunger, than in a future without climate change. Most affected would be populations in poor areas in sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia, especially those who rely on agriculture for their livelihoods. Future food security in many countries will worsen if no action is taken today.

“The benefits of adaptation outweigh the costs of inaction by very wide margins,” emphasized Mr. Graziano da Silva.

However, it is agriculture, including forestry, fisheries and livestock production, which is contributing to a warmer world by generating around a fifth of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, agriculture must both contribute more to combating climate change while bracing to overcome its impacts, the report says.

Time for action

Without action, agriculture will continue to be a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions. But by adopting climate-smart practices and increasing the capacity of soils and forests to sequester carbon, emissions can be reduced while stepping up food production to feed the world’s growing population, the report says.

The report provides evidence that adoption of climate-smart practices, such as the use of nitrogen-efficient and heat-tolerant crop varieties, zero-tillage and integrated soil fertility management would boost productivity and farmers’ incomes. Widespread adoption of nitrogen-efficient practices alone would reduce the number of people at risk of undernourishment by more than 100 million, the report estimates.

It also identifies avenues to lower emission intensity from agriculture. Water-conserving alternatives to the flooding of rice paddies can slash methane emissions by 45 per cent, while emissions from the livestock sector can be reduced by up to 41 per cent through the adoption of more efficient practices.

“2016 should be about putting commitments into action,” urged Mr. Graziano da Silva, noting the international community last year agreed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement on climate change, which is expect to come into force early next month. Agriculture will be high on the agenda at the 22nd Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), known by the shorthand COP 22, in Morocco starting on 7 November.

Helping small farmers adapt to climate change risks is critical

Developing countries are home to around half a billion small farm families who produce food and other agricultural products in greatly varying agro-ecological and socio-economic conditions. Solutions have to be tailored to those conditions; there is no one-size-fits-all fix.

Helping smallholders adapt to climate change risks is critical for global poverty reduction and food security. Close attention should be paid to removing obstacles they may face and fostering an enabling environment for individual, joint and collective action, according to the report.

FAO urges policy makers to identify and remove such barriers. These obstacles can include input subsidies that promote unsustainable farming practices, poorly aligned incentives and inadequate access to markets, credit, extension services and social protection programmes, and often disadvantage women, who make up to 43 per cent of the agricultural labour force.

The report stresses that more climate finance is needed to fund developing countries’ actions on climate change. International public finance for climate change adaptation and mitigation is growing and, while still relatively small, can act as a catalyst to leverage larger flows of public and private investments. More climate finance needs to flow to sustainable agriculture, fisheries and forestry to fund the large-scale transformation and the development of climate-smart food production systems.

This article was originally posted here.

A growing global population and changing diets are driving up the demand for food. Production is struggling to keep up as crop yields level off in many parts of the world, ocean health declines, and natural resources—including soils, water and biodiversity—are stretched dangerously thin. One in nine people suffers from chronic hunger and 12.9 percent of the population in developing countries is undernourished. The food security challenge will only become more difficult, as the world will need to produce about 70% more food by 2050 to feed an estimated 9 billion people.

The challenge is intensified by agriculture’s extreme vulnerability to climate change. Climate change’s negative impacts are already being felt, in the form of reduced yields and more frequent extreme weather events, affecting crops and livestock alike. Substantial investments in adaptation will be required to maintain current yields and to achieve the required production increases

Agriculture is also a major part of the climate problem. It currently generates 25% of total greenhouse gas emissions. Without action, that percentage could rise substantially as other sectors reduce their emissions.

Producing More with Less

Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) is an integrated approach to managing landscapes—cropland, livestock, forests and fisheries--that address the interlinked challenges of food security and climate change. CSA aims to simultaneously achieve three outcomes:

1. Increased productivity: Produce more food to improve food and nutrition security and boost the incomes of 75% of the world’s poor, many of whom rely on agriculture for their livelihoods.

2. Enhanced resilience: Reduce vulnerability to drought, pests, disease and other shocks; and improve capacity to adapt and grow in the face of longer-term stresses like shortened seasons and erratic weather patterns.

3. Reduced emissions: Pursue lower emissions for each calorie or kilo of food produced, avoid deforestation from agriculture and identify ways to suck carbon out of the atmosphere.

While built on existing knowledge, technologies, and principles of sustainable agriculture, CSA is distinct in several ways. First, it has an explicit focus on addressing climate change. Second, CSA systematically considers the synergies and tradeoffs that exist between productivity, adaptation and mitigation, in order to capitalize on the benefits of integrated and interrelated results.

Find out more about CSA basics, planning, financing, investing and more in the online guide to CSA developed in collaboration with the Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security (CCAFS) of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR): https://CSA.guide.

Climate-Smart Agriculture and the World Bank Group

The World Bank Group (WBG) is currently scaling up climate-smart agriculture and in its Climate Change Action Plan has committed to 100 percent of agricultural operations being climate-smart by 2019. The WBG portfolio will also increase its focus on impact at scale and be rebalanced to have a greater focus on adaptation and resilience. To enable these commitments, we are screening all IDA projects for climate risks, and will continue to develop and mainstream metrics and indicators to measure outcomes, and account for greenhouse gas emissions in our projects and operations. These actions will help our client countries implement their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in the agriculture sector, and will contribute to progress on the Sustainable Development Goals for climate action, poverty, and the eradication of hunger.

The World Bank Group also backs research programs such as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), which develops climate smart technologies and management methods, early warning systems, risk insurance and other innovations that promote resilience and combat climate change.

For example, Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Country Profiles bridge a knowledge gap by providing clarity on CSA terminology, components, relevant issues, and how to contextualize it under different country conditions. The knowledge product is also a methodology for assessing a baseline on climate-smart agriculture at the country level (both national and sub-national) that can guide climate smart investments and development.

Working Toward Food and Nutrition Security, while Curbing GHG Emissions

The Bank’s support of CSA is making a difference across the globe:

In Uruguay, the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources and Climate Change (DACC) project is supporting sustainable intensification through a number of initiatives including the establishment of an Agricultural Information and Decision Support System (SNIA) and the preparation of soil management plans.

The Morocco Inclusive Green Growth project supports the national green growth agenda by increasing the supply of agrometeorological information and facilitating the diffusion of new, resilience-building technologies such as direct seeders.

In Senegal, the West Africa Agricultural Productivity Program (WAAPP) and its partners have developed seven new high-yielding, early-maturing, drought resistant varieties of sorghum and millet. Released in 2012, these varieties are being widely diffused to farmers and show positive yield result.

In Ethiopia, the Humbo Assisted Natural Regeneration Project has helped restore 2,700 hectares of biodiverse native forest, which has boosted production of income-generating wood and tree products such as honey and fruit.

African farmers who have adopted evergreen agriculture are reaping impressive results without the use of costly fertilizers. Crop yields often increase by 30 percent and sometimes more. In Zambia, for example, maize yields tripled when grown under Faidherbia trees..

This blog post was originally posted here.

With water shortages exacerbating inequalities and causing damage to economies, making sure the commodity is properly valued by all is essential.

Water is essential for life, whether to irrigate crops, to manufacture goods, or for drinking, washing and cleaning. But the intensification of climate change, a growing population and increasing demands from cities, agriculture and industry – coupled with poor water governance – is driving acute water shortages around the world.

The World Bank predicts that by 2050 this scarcity will deliver a significant hit to the economies of Africa, central Asia and the Middle East, taking double digits off their GDP.

To address these challenges and ensure that every person, country and business has enough, it is essential to determine the true value of water throughout the supply chain. But how?

This was the question debated during a panel discussion, hosted by the Guardian and supported by SABMiller, at the World Water Week conference in Stockholm, Sweden, which was organised in association with the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI).

Lack of awareness

The panel was unanimous that water is not valued in the way it should be. Lack of awareness was suggested as a likely cause.

“In places where farmers have been hit by drought to the point that it’s impacted their livelihoods, water has become a valued resource,” said Paul Reig, senior associate of the Water Programme and Business Centre at the World Resources Institute. “It is places that haven’t suffered this kind of impact that lack awareness.”

Reig has been working with Valuing Nature, a sustainability consultancy, to understand the value of water in terms of the cost of delivering it in socially, environmentally and economically beneficial ways. “We think that by understanding the total cost, it could inform the level of investment needed to reach those conditions, as well as the largest impacts that are impeding their achievement,” he said.

Thirsty agriculture

The panel agreed that the agriculture sector has a long way to go before it adequately values water. “Agriculture is the largest consumer and the largest polluter of water,” said Reig. “Despite this, it’s difficult to ask farmers to pay for water when they struggle to make a living.”

John Vidal, the Guardian’s Environment editor who chaired the debate, asked whether farmers need to think differently about how they grow and irrigate crops, if they are unwilling or unable to pay for water.

“I think it’s already happening,” said Anton Earle, director of SIWI’s African Regional Centre. The government of Botswana is looking at ways to introduce a water charge for farmers and the farmers SIWI speaks to there say they are already using efficient techniques for irrigation to reduce the cost of powering pumps, he said.

Speaking companies’ language

It is not only in agriculture, however, where operations and processes need to be more water efficient.

SIWI has been working with Swedish textile companies to encourage their production plants in countries such as Bangladesh, China and Ethiopia to place greater value on water. “We talk to these factories and say: ‘You’re using and polluting many of the water resources in the local area – you should change your practices’, but factory owners would rather sell to a business that is less pushy,” said Earle.

Instead, the key was to find the right language businesses could respond to. “We asked them about their major costs and they consistently pointed to energy and the chemicals used to dye textiles. We told them we could introduce processes that would reduce those costs,” said Earle. “So instead of dyeing fabric three or four times and releasing the water, they do it once, capture the chemicals and reuse them. Improving water use is a side effect but the entry point had to be something that the corporates could really relate to.”

But individual corporate action does not necessarily mean water is being better valued overall. André Fourie, head of water security and environmental value at SABMiller, described the company’s work with barley farmers in India, where he says agriculture accounts for 80% of water consumption. “By having better irrigation – drip irrigation [where water is directed at the plant’s root], for example – they save water. But we’ve also seen that the water they save is used by someone else, so we haven’t actually solved the problem.”

One of the most effective ways for companies to determine the value of water, says Fourie, is to develop a better understanding of what it costs throughout different parts of the business. “By having one price [for water] in our thinking it makes our decisions quite blunt. Take a brewery: the water that comes into it has one price, but if the brewery treats it the water is worth more.”

Should we pay more for water?

One of the key challenges in securing a long-term supply of water is finding sustainable streams of finance and working out who should bear the cost.

“In many cases, there is a cultural issue around making profit from water, even in countries where the private sector has played a strong role in different parts of the economy,” said Earle.

When it was suggested to the National Treasury of South Africa that the country’s wastewater treatment could be handled by the private sector on the condition that the business could sell off the treated water, the idea, said Earle, was not met with open arms.

In some areas, however, many of the poorest people have to buy water from vendors, tankers and other informal providers, and spend as much as 10 times more than someone who has a reliable connection in the home. While this situation reveals deep inequalities, it also shows that there is a willingness to pay.

Monika Freyman, director of Investor Water Initiatives at non-profit Ceres, agreed that asking domestic users to pay for water could be a way of increasing the value placed on it, as well as leveraging the money needed to secure supply.

“Many investors, when they look at private solutions or public-private partnerships, are beginning to ask: ‘How can we ensure that those at the bottom of the pyramid can afford and have access to water?’ I think privatisation can work but you have to have pretty strong policies and stewardship from the regulators to go with it.”

Freyman believes that the corporate and investment community can value water better by understanding the risks of inefficient water management. “Many companies are beginning to assess the money they’re leaving on the table by not getting water management right,” she said. “In the past, the investment community was obsessed with the volumes of water they were using, but I think the bigger question now is: what are the lost opportunities around not understanding and managing water well?”

This article was originally posted on the Guardian.

Mature trees clean air, lower stress, boost happiness, reduce flood risk – and even save municipal money. So why are they cut down when cities develop – and how should the UN’s new urban agenda protect them?

Sheffield residents campaigned to save mature lime trees which the city council earmarked to be felled. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

The skyline along Manhattan’s Upper Fifth Avenue, where it flanks Central Park, is dominated by vast, verdant clouds of American elm trees. Their high-arched branches and luminous green canopies form – as historian Jill Jones puts it – “a beautiful cathedral of shade”. When she started researching her new book, Urban Forests, she’d have struggled to identify the species – but now, she says, “when I see one, I say ‘Oh my goodness, this is a rare survivor,’ and deeply appreciate the fact that it’s there.”

The American elm was once America’s most beloved and abundant city tree. It liked urban soil, and its branches spread out a safe distance above traffic, to provide the dappled shade that cities depended on before air conditioning.

Now, however, most of the big, old elms have been wiped out by Dutch elm disease. Many of them were replaced by ash, which have in turn been killed by another imported pest: the emerald ash borer. By the 1970s, writes Jones, much of America’s urban tree cover had fallen victim to “disease, development and shrinking municipal budgets”.

Thousands of miles away, in Bangkok, the main threat is construction work. After a group of residents tried in vain to save several mature trees on their lane, which were felled to make way for a car park, they formed a tree advocacy group, the Big Trees Project.

Within weeks, membership swelled to 16,000. Forestry officer at the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), Simone Borelli tells me of similar tree advocacy groups in Malaysia, India and Central African Republic, where the capital, Bangui, has “grown out of the forest and is eating it up”.

Greenery on the campus of Mohammed VI Polytechnic University in Ben Guerir, Morocco. (Photo by Connect4Climate)

This month will see representatives from the world’s cities convene in Quito, Ecuador, for the United Nations conference on sustainable urban development,Habitat III. An agreement called the New Urban Agenda will be launched, to address the challenges facing a growing global urban population that already accounts for over 50% of us.

The document is littered with references to green spaces being essential for mental and physical health, community building and performing urgent ecological tasks. Research has turned up fascinating evidence as to why town councils, planners and developers – in whose hands the fate of urban trees lies – should take heed.

Until recently, says Jones, city officials saw trees as “expensive ornaments”. But what is now known about the ecological services that trees provide is staggering.

Trees can cool cities by between 2C and 8C. When planted near buildings, trees can cut air conditioning use by 30%, and, according to the UN Urban Forestry office, reduce heating energy use by a further 20-50%. One large tree can absorb 150kg of carbon dioxide a year, as well as filter some of the airborne pollutants, including fine particulates.

It’s hard to put a price on how an avenue of plane trees can muffle the roar of a main road, although trees do on average increase the value of property by 20%. Perhaps money does grow on them after all.

When the New York City park department measured the economic impact of its trees, the benefits added up to $120m a year. (Compare that to the $22m annual parks department expenditure.) There were $28m worth of energy savings, $5m worth of air quality improvements and $36m of costs avoided in mitigating storm water flooding. If you look at a big tree, says Jones, “it’s intercepting 1,432 gallons of water in the course of a year.”

Use of the open source software, i-Tree, has spread all over the world (from China to the UK, via Brazil and Taiwan) to assess canopy size – ideally, cities should have 40% coverage – and calculate its economic worth. “To be able to monetise those benefits is really useful,” says Jones. “Trees are economic drivers. Everyone knows, if you look at fancy neighbourhoods, they are the ones with the most trees.” By the same token, she observes that underprivileged neighbourhoods are often also undercanopied.

Humans are drawn to trees by more than aesthetics. It can bring down cortisol levels in walkers, which means less stress. The effect on our brains is a subject that fascinates UK-based GP and public health expert William Bird.

“The parts of our brain we use change when we connect with nature,” he says. Even in lab-based studies, MRI scanning shows that when viewing urban scenes, blood flow to the amygdala – the “fight-or-flight” part of the brain – increases. Our brains view cities as hostile environments. Natural scenes, by contrast, light up the anterior cingulate and the insula, where empathy and altruism happen.

“In areas with more trees,” says Bird, “people get out more, they know their neighbours more, they have less anxiety and depression.” (Here in the UK, the annual mental health bill is around £70bn.) “Being less stressed,” he continues, “gives them more energy to be active”. But you can’t fob people off with an empty playing field, he says. “People won’t want to go there. We are still programmed as hunter gatherers who look for trees, biodiversity, water and safety.”

Research suggests people are less violent when they live near trees. One of the oft-cited examples is a study that looked at women in a Chicago housing estate. Those who lived near the trees reported less mental fatigue and less violent tendencies than those in barren areas of the same estate.

‘In areas with more trees, people get out more’: a tree-lined street in Gothenburg. Photograph: Souvid Datta for the Guardian

“We still know very little about the mechanisms linking trees and health,” says Geoffrey Donovan, research forester with the US Forest Service. But there are theories. One is that nature is so mentally restorative that it gives our minds a rest from the forced, direct attention that modern life and urban environments increasingly call for. It relieves mental fatigue.

A tree psychology study that particularly tickles Jones was done in Toronto bypsychology professor Marc Berman, using data sets from the national health system. “He discovered that, if you have 10 more trees on a city block, it improves health perception as much as having £10,000 more in income, or feeling seven years younger,” she says.

Perhaps one of the most striking studies on urban trees is one that showed that they reduce health inequality. In 2008, Rich Mitchell, a public health professor at the University of Glasgow, compared income deprivation and green space exposure across England and his study found “health inequalities related to income deprivation in all-cause mortality and mortality from circulatory diseases were lower in populations living in the greenest areas”.

Back at the US Forest Service, Donovan refers to trees as “a matter of life and death”. “I looked at the impact of trees on birth outcomes and found that mothers with more trees within 50m of their homes are less likely to have underweight babies,” he says. For another study, he looked at mortality rates in areas which have lost millions of trees to emerald ash borer, and identified “a corresponding increase in human mortality”.

The value we place on trees and nature is informed by childhood experience. Children growing up dislocated from nature results in, say some researchers, an “extinction of experience”. These children will ultimately understand and value nature less. “This means,” writes Bird, “that each generation will pass on less experience of the natural environment – and as policymakers and future environmentalists they will have a poorer understanding of nature and so give it less value”.

Which would not bode well for the FAO Forestry Department’s vision of “greener, happier, healthier cities”. As Jones says, “being an amateur tree appreciator, as I now am, really does transform your enjoyment of being out and about”.

This article was originally posted on the Guardian.

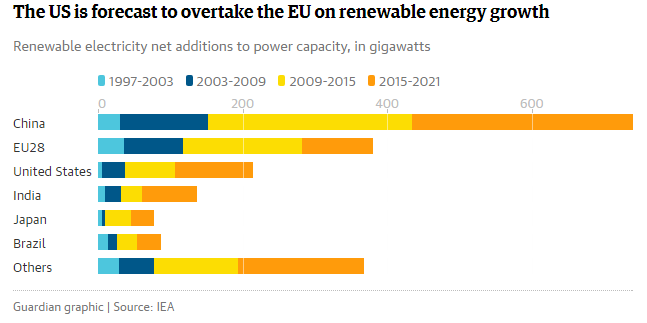

The "Climate Action Tracker" is an independent science-based assessment, which tracks the emission commitments and actions of countries. The website provides an up-to-date assessment of individual national pledges, targets and INDCs and currently implemented policy to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

The CAT tracks 32 countries covering around 80% of global emissions. All the biggest emitters and a representative sample of smaller emitters covering about 80% of global emissions and approximately 70% of global population. The national actions we track are:

- Effect of current policies on emissions: The policies a government has implemented or enacted and how these are likely to affect national emission over the time period to 2030, and where possible beyond.

- Impact of pledges, targets and INDCs (link) on national emissions over the time period to 2030, and where possible beyond.

- Fair share and comparability of effort: Whether a government is doing its “fair share” compared with others towards the global effort to limit warming below 2?C.

CAT calculates global warming consequence and emissions gaps. The Climate Action Tracker assesses the total global effort of INDCs, pledges and current policies.

Rating countries

Governments have agreed to hold warming to below 2°C. The focus of emission reduction proposals to be submitted in INDCs during 2015 is for governments to put forward their proposed contributions to a “fair sharing” of effort to move global emissions downward in the period 2020-2025-2030.

The Climate Action Tracker rates INDCs, pledges and current policies against whether they are consistent with a country's fair share effort to holding warming to below 2°C.

The CAT “Effort Sharing” assessment methodology applies state-of-the art scientific literature on how to compare the fairness of government efforts and INDC proposals against the level and timing of emission reductions needed to hold warming to below 2°C. The main focus is on the period 2020, 2025 and 2030.

Check the Individual country assessments on this list.

In September 2015, 193 world leaders agreed to 17 Global Goals for Sustainable Development. If these Goals are completed, it would mean an end to extreme poverty, inequality and climate change by 2030.

Our governments have a plan to save our planet…it’s our job to make sure they stick to it.

The Global Goals are only going to work if we fight for them and you can’t fight for your rights if you don’t know what they are. We believe the Goals are only going to be completed if we can make them famous.

[video: https://youtu.be/Mdm49_rUMgo]

Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Climate change is now affecting every country on every continent. It is disrupting national economies and affecting lives, costing people, communities and countries dearly today and even more tomorrow.

"This is not a partisan debate; it is a human one. Clean air and water, and a liveable climate are inalienable human rights. And solving this crisis is not a question of politics. It is our moral obligation.", Leonardo DiCaprio

Targets

- Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries

- Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning

- Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning

- Implement the commitment undertaken by developed-country parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to a goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion annually by 2020 from all sources to address the needs of developing countries in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation and fully operationalize the Green Climate Fund through its capitalization as soon as possible

- Promote mechanisms for raising capacity for effective climate change-related planning and management in least developed countries and small island developing States, including focusing on women, youth and local and marginalized communities

Know more about the 13 Global Goal for Sustainable Development.

The future of our Planet is in our hands. WWF's Living Planet Report 2016 shows the scale of the challenge - and what we can do about it.

Global biodiversity is declining at an alarming rate, putting the survival of other species and our own future at risk. The latest edition of WWF’s Living Planet Report brings home the enormity of the situation - and how we can start to put it right. The Living Planet Index reveals that global populations of fish, birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles declined by 58 per cent between 1970 and 2012. We could witness a two-thirds decline in the half-century from 1970 to 2020 – unless we act now to reform our food and energy systems and meet global commitments on addressing climate change, protecting biodiversity and supporting sustainable development.

ENTERING A NEW ERA

Human activities are pushing our planet into uncharted territory. In fact, there’s strong evidence that we’ve entered a new geological epoch shaped by human actions: “the Anthropocene”. The planet’s inhabitants – Homo sapiens included – face an uncertain future.

The loss of biodiversity is just one of the warning signs of a planet in peril. The Ecological Footprint – which measures our use of goods and services generated by nature – indicates that we’re consuming as if we had 1.6 Earths at our disposal. In addition, research suggests that we’ve already crossed four of nine “Planetary Boundaries” – safe thresholds for critical Earth system processes that maintain life on the planet.

[video: https://youtu.be/VMsxHaeyzNs]

TOWARD A RESILIENT FUTURE

But if humans can change the planet so profoundly, then it’s also in our power to put things right. That will require new ways of thinking, smarter methods of producing, wiser consumption and new systems of finance and governance.

The Living Planet Report provides possible solutions – including the fundamental changes required in the global food, energy and finance systems to meet the needs of current and future generations.

INSPIRING STORIES

There are reasons for hope. All over the world there are examples of successful restoration of ecosystems, recovery of species and creation of resilient and hospitable places for wildlife and people.

Here we highlight several inspiring cases.

DOWNLOAD THE SUMMARY

Law, Justice and Development Week (LJD Week) is an annual event organized by the Legal Vice Presidency of the World Bank in collaboration with the Global Forum on Law, Justice and Development, an international knowledge exchange platform of over 170 partners engaged in legal aspects of development.