Panel Discussion - Climate Action for Sustainable Development #All4TheGreen

Climate Action for Sustainable Development Panel Discussion at #All4TheGreen - Mobilizing Climate Science Event, in Bologna with:

Panel Discussion - Climate Knowledge For Ambitious Action #All4TheGreen

Climate Knowledge For Ambitious Action Panel Discussion at #All4TheGreen - Mobilizing Climate Science Event, in Bologna with:

#All4TheGreen 2018 - Opening Remarks

Opening Remarks of the #All4TheGreen - Mobilizing Climate Science Event, in Bologna with:

|

World Meteorological Day: Weather-ready, climate-smart

By

Weather-ready climate-smart is the theme of this year’s World Meteorological Day on 23 March. It highlights the need for informed planning for day-to-day weather and hazards like floods as well as for naturally occurring climate variability and long-term climate change.

The World Meteorological Organization selected the slogan because it underlines the central role of national meteorological services in decisions as diverse as when to carry an umbrella, whether to seek shelter or evacuate from a major storm, when to plant and harvest crops, and how to plan urban infrastructure and water management decades ahead.

“Now more than ever, we need to be weather-ready, climate-smart and water-wise. This is because the ever-growing global population faces a wide range of hazards such as tropical cyclone storm surges, heavy rains, heatwaves, droughts and many more. Long-term climate change is increasing the intensity and frequency of extreme weather and climate events and causing sea level rise and ocean acidification. Urbanization and the spread of megacities means that more of us are exposed and vulnerable."

Petteri Taalas, WMO Secretary-General

Annual Statement on State of Global Climate

“The start of 2018 has continued where 2017 left off – with extreme weather, which has claimed lives and destroyed livelihoods. The Arctic experienced unusually high temperatures, whilst densely populated areas in the northern hemisphere were gripped by bitter cold and damaging winter storms. Parts of Australia and Argentina suffered extreme heatwaves, whilst drought continues in Somalia and the South African city of Cape Town struggles with acute water shortages,” said Mr Taalas.

The 2017 hurricane season was the costliest ever for the United States – and eradicated decades of developments gains in small islands in the Caribbean such as Dominica. Floods uprooted millions of people on the Asian subcontinent, whilst drought is exacerbating poverty and increasing migration pressures in the Horn of Africa, according to the Annual Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2017.

The statement confirmed that 2017 was one of the three warmest years on record, and was the warmest year without an El Niño. Because the societal and economic impacts of climate change have become so severe, WMO has partnered with other United Nations organizations to include information on how climate has affected migration patterns, food security, health and other sectors.

Multi-Hazard Early Warnings

One of the top priorities of WMO and National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) is to protect lives, livelihoods and property from the risks related to weather, climate and water events.

The dramatic reduction in the lives lost due to severe weather events in the last thirty years has been largely attributed to the significant increase in accuracy of weather forecasting and warnings and improved coordination with disaster management authorities. Thanks to developments in numerical weather prediction, a 5-day forecast today is as good as a 2-day forecast twenty years ago.

“But forecasts of what the weather will BE are no longer enough and increasingly the focus is on what the weather will DO. WMO is therefore working to establish a global and standardized multi-hazard alert system in collaboration with National Meteorological and Hydrological Services worldwide", said Mr Taalas.

In addition, WMO worked with a wide range of partners to draw up a multi-hazard early warning systems checklist. Published on World Meteorological Day, the checklist is an important, practical tool to boost resilience.

To be effective, early warning systems need to actively involve the people and communities at risk from a range of hazards, facilitate public education and awareness of risks, effectively disseminate messages and warnings and ensure there is a constant state of preparedness and that early action is enabled.

The Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems Checklist is structured around these four key elements of early warning systems. It aims to be a simple list of the main components and actions to which national governments, community organizations and partners within and across all sectors can refer when developing or evaluating early warning systems.

Through the lens of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, it incorporates the acknowledged benefits of multi-hazard early warnings systems, disaster risk information and enhanced risk assessments. It is anticipated that this Checklist will be updated as technologies, advances in multihazard early warning systems and feedback from the users is received.

The publication was prepared by the partners of the International Network for Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems and is a key outcome of the first Multi-Hazard Early Warning Conference that took place in Cancún, Mexico in May 2017.

World Meteorological Day takes place on 23 March to commemorate the entry into force, on that date in 1950, of the convention creating the WMO.

|

The future of forests and climate change: what have we achieved so far and what’s next?

By

Join us to learn why tropical forests are essential for both climate stability and sustainable development

At the Paris climate talks in 2015, about 190 countries made clear commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase their resilience to climate change. Better forest and land management figured prominently among their national plans.

To mark the anniversary of the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), which is pioneering large scale emission reductions programs, a panel discussion will focus on how those pledges are becoming a reality, the current challenges, and how we can continue to mobilize support for forest conservation, climate change mitigation and improved livelihoods.

After the event, we’ll catch up with the speakers about how to best seize the policy will and financing opportunities of the international forest and climate agenda and put them to work to deliver big forest conservation and climate change mitigation wins. In one interview, a leading researcher will make the case for why tropical forests are essential for both climate stability and sustainable development, and about the timeliness, affordability, and feasibility of scaling up funding for reducing deforestation. You’ll hear how an NGO is working on advocacy for environmentally effective and economically sound climate and forest policies. And an Indigenous Peoples representative will speak about the urgency of action – in and outside forests – to preserve livelihoods, save lives and slow climate change and how multi-stakeholder platforms are making this possible.

Relive the Facebook Live sessions on the Connect4Climate Facebook page

Live interviews

Ellysar Baroudy, Coordinator for the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, tells us about the importance of forests for development

Ellysar Baroudy, Coordinator for the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, tells us about the importance of forests for development

Frances Seymour, Distinguished Senior Fellow, World Resources Institute

Frances Seymour, Distinguished Senior Fellow, World Resources Institute

Glenn Prickett, Chief External Affairs Officer, The Nature Conservancy

Glenn Prickett, Chief External Affairs Officer, The Nature Conservancy

Banner and thumbnail photo credits to the World Bank

|

State of Climate in 2017 – Extreme weather and high impacts

By

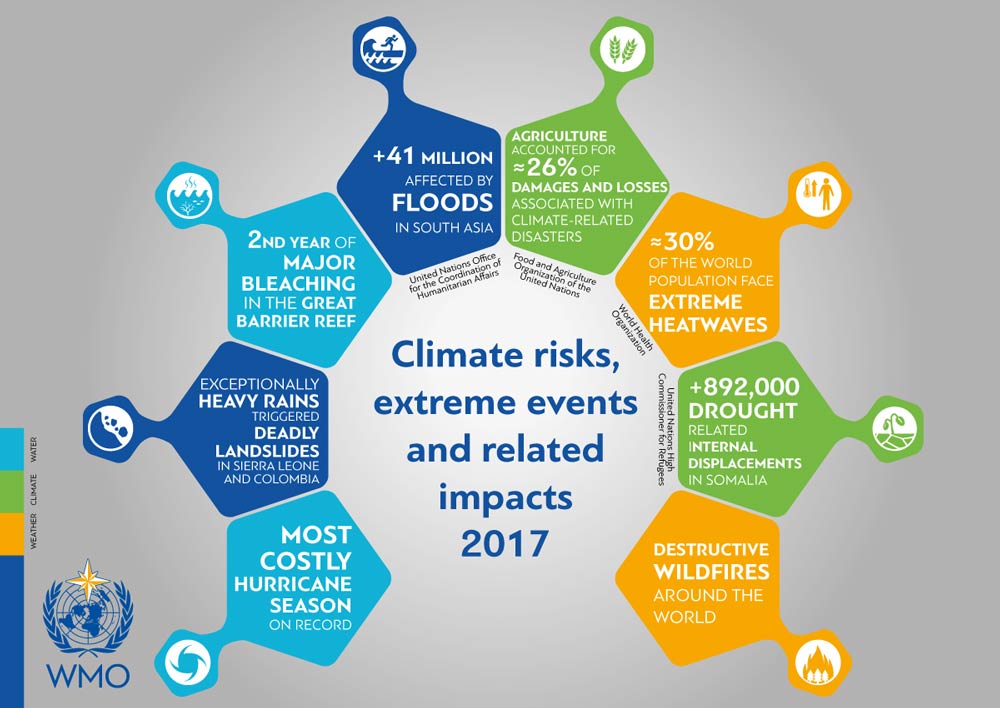

The very active North Atlantic hurricane season, major monsoon floods in the Indian subcontinent, and continuing severe drought in parts of east Africa contributed to 2017 being the most expensive year on record for severe weather and climate events.

The high impact of extreme weather on economic development, food security, health and migration was highlighted in the WMO Statement on State of the Global Climate in 2017. Compiled by the World Meteorological Organization with input from national meteorological services and United Nations partners, the report provides detailed information to support the international agenda on disaster risk reduction, sustainable development and climate change.

The Statement, now in its 25th year, was published for World Meteorological Day on 23 March. It confirmed that 2017 was one of the three warmest years on record and the warmest not influenced by an El Niño event. It also examined other long-term indicators of climate change such as increasing carbon dioxide concentrations, sea level rise, shrinking sea ice, ocean heat and ocean acidification.

Global mean temperatures in 2017 were about 1.1 °C above pre-industrial temperatures. The five-year average 2013–2017 global temperature is the highest five-year average on record. The world’s nine warmest years have all occurred since 2005, and the five warmest since 2010.

"The start of 2018 has continued where 2017 left off – with extreme weather claiming lives and destroying livelihoods. The Arctic experienced unusually high temperatures, whilst densely populated areas in the northern hemisphere were gripped by bitter cold and damaging winter storms. Australia and Argentina suffered extreme heatwaves, whilst drought continued in Kenya and Somalia, and the South African city of Cape Town struggled with acute water shortages."

Petteri Taalas, WMO Secretary-General

“Since the inaugural Statement on the State of the Global Climate, in 1993, scientific understanding of our complex climate system has progressed rapidly. This includes our ability to document the occurrence of extreme weather and climate events, the degree to which they can be attributed to human influences, and the correlation of climate change with epidemics and vector-borne diseases,” said Mr Taalas.

“In the past quarter of a century, atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide have risen from 360 parts per million to more than 400 ppm. They will remain above that level for generations to come, committing our planet to a warmer future, with more weather, climate and water extremes,” said Mr Taalas.

Direct measurements of atmospheric CO2 over the past 800 000 years showed natural variations between 180 and 280 ppm. “This demonstrates that today’s CO2 concentration of 400 ppm exceeds the natural variability seen over hundreds of thousands of years,“ said the Statement.

Socio-economic impacts

2017 was a particularly severe year for disasters with high economic impacts. Munich Re assessed total disaster losses from weather and climate-related events in 2017 at US$ 320 billion, the largest annual total on record (after adjustment for inflation).

Fuelled by warm sea surface temperatures, the North Atlantic hurricane season was the costliest ever for the United States and eradicated decades of developments gains in small islands in the Caribbean such as Dominica. The National Centers for Environmental Information estimated total U.S. losses from Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria at US$ 265 billion. The World Bank estimates Dominica’s total damages and losses from the hurricane at US$ 1.3 billion or 224% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Climate impacts hit vulnerable nations especially hard, as evidenced in a recent study by the International Monetary Fund, which warned that a 1 °C increase in temperature would cut significantly economic growth rates in many low-income countries.

The overall risk of heat-related illness or death has climbed steadily since 1980, with around 30% of the world’s population now living in climatic conditions that deliver potentially deadly temperatures at least 20 days a year, according to information from the World Health Organization quoted in the Statement. It also included a section on the relationship between climate and the Zika epidemic in the Americas in 2014–2016.

In 2016, weather-related disasters displaced 23.5 million people. Consistent with previous years, the majority of these internal displacements were associated with floods or storms and occurred in the Asia-Pacific region.

Massive internal displacement in the context of drought and food insecurity continues across Somalia. From November 2016 to December 2017, 892 000 drought-related displacements were recorded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). In the Horn of Africa, the failure of the 2016 rainy season was followed by a harsh January–February 2017 dry season, and a poor March-to-May rainy season. In Somalia, as of June 2017, more than half of the cropland was affected by drought, and herds had reduced by 40–60% since December 2016 due to increased mortality and distress sales, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Food Programme.

Floods affected the agricultural sector, especially in Asian countries. Heavy rains in May 2017 triggered severe flooding and landslides in south-western areas of Sri Lanka. The negative impact of floods on crop production further aggravated the food security conditions in the country already stricken by drought, according to FAO and WFP.

The oceans

Global sea surface temperatures in 2017 were somewhat below the levels of 2015 and 2016, but still ranked as the third warmest on record. Ocean heat content, a measure of the heat in the oceans through their upper layers down to 2 000 meters, reached new record highs in 2017.

The Statement said that the magnitude of almost all of individual components of sea level rise has increased in recent years, in particular melting of the polar ice sheets, mostly in Greenland and to a lesser extent Antarctica.

For the second successive year, above-average sea surface temperatures off the east coast of Australia resulted in significant coral bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef.

The Climate Statement contained a special section on ocean acidification. Over the past 10 years, various studies have confirmed that ocean acidification is directly influencing the health or coral reefs, the success, quality and taste of aquaculture raised fish and seafood, and the survival and calcification of several key organisms. These alterations have cascading effects within the food web, which are expected to result in increasing impacts on coastal economies, according to UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission.

Cryosphere

Sea ice extent was well below the 1981–2010 average throughout 2017 in both the Arctic and Antarctic. The winter maximum of Arctic sea ice was the lowest winter maximum in the satellite record. The summer minimum was the 8th lowest on record, but a slow freeze-up saw sea ice extent once again near record lows for December.

Antarctic sea ice extent was at or near record low levels throughout the year.

The Greenland ice sheet mass balance change from September to December 2017 was close to average. Despite the gain in overall ice mass this year, it is only a small departure from the trend over the past two decades, with the Greenland ice sheet having lost approximately 3 600 billion tons of ice mass since 2002.

Northern Hemisphere snow cover extent was near or slightly above the 1981–2010 average for most of the year.

Information used in this report is sourced from a large number of National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) and associated institutions, as well as Regional Climate Centres, the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), the Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) and Global Cryosphere Watch. Information has also been supplied by a number of other United Nations agencies, including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC-UNESCO).

WMO uses datasets (based on monthly climatological data from observing sites) from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and the United Kingdom’s Met Office Hadley Centre and the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit in the United Kingdom.

It also uses reanalysis datasets from the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts and its Copernicus Climate Change Service, and the Japan Meteorological Agency. This method combines millions of meteorological and marine observations, including from satellites, with models to produce a complete reanalysis of the atmosphere. The combination of observations with models makes it possible to estimate temperatures at any time and in any place across the globe, even in data-sparse areas such as the polar regions.

|

Climate Change Could Force Over 140 Million to Migrate Within Countries by 2050: World Bank Report

By

The worsening impacts of climate change in three densely populated regions of the world could see over 140 million people move within their countries’ borders by 2050, creating a looming human crisis and threatening the development process, a new World Bank Group report finds.

But with concerted action - including global efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions and robust development planning at the country level – this worst-case scenario of over 140m could be dramatically reduced, by as much as 80 percent, or more than 100 million people.

The report, Groundswell – Preparing for Internal Climate Migration, is the first and most comprehensive study of its kind to focus on the nexus between slow-onset climate change impacts, internal migration patterns and, development in three developing regions of the world: Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.

It finds that unless urgent climate and development action is taken globally and nationally, these three regions together could be dealing with tens of millions of internal climate migrants by 2050. These are people forced to move from increasingly non-viable areas of their countries due to growing problems like water scarcity, crop failure, sea-level rise and storm surges.

Click on the image to see the infographic

These “climate migrants” would be additional to the millions of people already moving within their countries for economic, social, political or other reasons, the report warns.

World Bank Chief Executive Officer Kristalina Georgieva said the new research provides a wake-up call to countries and development institutions.

"We have a small window now, before the effects of climate change deepen, to prepare the ground for this new reality. Steps cities take to cope with the upward trend of arrivals from rural areas and to improve opportunities for education, training and jobs will pay long-term dividends. It’s also important to help people make good decisions about whether to stay where they are or move to new locations where they are less vulnerable."

Kristalina Georgieva, World Bank Chief Executive Officer

The research team, led by World Bank Lead Environmental Specialist Kanta Kumari Rigaud and including researchers and modelers from CIESIN Columbia University, CUNY Institute of Demographic Research, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research - applied a multi-dimensional modeling approach to estimate the potential scale of internal climate migration across the three regions.

They looked at three potential climate change and development scenarios, comparing the most “pessimistic” (high greenhouse gas emissions and unequal development paths), to “climate friendly” and “more inclusive development” scenarios in which climate and national development action increases in line with the challenge. Across each scenario, they applied demographic, socioeconomic and climate impact data at a 14-square kilometer grid-cell level to model likely shifts in population within countries.

This approach identified major “hotspots” of climate in- and out-migration - areas from which people are expected to move and urban, peri-urban and rural areas to which people will try to move to build new lives and livelihoods.

“Without the right planning and support, people migrating from rural areas into cities could be facing new and even more dangerous risks. We could see increased tensions and conflict as a result of pressure on scarce resources. But that doesn’t have to be the future. While internal climate migration is becoming a reality, it won’t be a crisis if we plan for it now.”

Kanta Kumari Rigaud, report’s team lead

The report recommends key actions nationally and globally, including:

Cutting global greenhouse gas emissions to reduce climate pressure on people and livelihoods, and to reduce the overall scale of climate migration;

Cutting global greenhouse gas emissions to reduce climate pressure on people and livelihoods, and to reduce the overall scale of climate migration;

Transforming development planning to factor in the entire cycle of climate migration (before, during and after migration);

Transforming development planning to factor in the entire cycle of climate migration (before, during and after migration);

Investing in data and analysis to improve understanding of internal climate migration trends and trajectories at the country level.

Investing in data and analysis to improve understanding of internal climate migration trends and trajectories at the country level.|

Meet the Human Faces of Climate Migration

By

A new World Bank report has found that by 2050 the worsening impacts of climate change in three densely populated regions of the world could see more than 140 million people move within their countries’ borders. With concerted action, however, including global efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions and robust development planning at the country level – this worst-case scenario could be dramatically reduced, by as much as 80 percent, or 100 million people.

The report identifies “hotspots” of climate in-and out-migration. These include climate-vulnerable areas from which people are expected to move, and locations into which people will try to move to build new lives and livelihoods.

People move for many reasons – economic, social, and political. Now, climate change has emerged as a major driver of migration, propelling increasing numbers of people to move from vulnerable to more viable areas of their countries to build new lives.

The newly released World Bank report, Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration, analyzes this recent phenomenon and projects forward to 2050. Focusing on three regions — Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America – the report warns that unless urgent climate and development action is taken, these three regions could be dealing with a combined total of over 140 million internal climate migrants by 2050. These people will be pushed out by droughts, failing crops, rising sea levels, and storm surges.

But there is still a way out: with concerted action – including global efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions, combined with robust development planning at the country level –the number of people forced to move due to climate change could be reduced by as much as 80 percent – or 100 million people.

"We have a small window now, before the effects of climate change deepen, to prepare the ground for this new reality. Steps cities take to cope with the upward trend of arrivals from rural areas and to improve opportunities for education, training and jobs will pay long-term dividends. It’s also important to help people make good decisions about whether to stay where they are or move to new locations where they are less vulnerable."

Kristalina Georgieva, World Bank Chief Executive Officer

Climate migrants: the human face of climate change

The report looks closely at three country examples: Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Mexico, all countries with very different climatic, livelihood, demographic, migration and development patterns.

It is worth taking a moment to remember that behind all trends there are real people with dreams, hopes, and aspirations. We met three people whose lives have been transformed in different ways as they have dealt with the impacts of climate change.

Watch Monoara Khatun's story

Monoara Khatun is a 23-year-old seamstress from Kurigram, Bangladesh. Her village has been flooded many times, and this has led to increasing unemployment and food scarcity.

“Floods come every year, but this year the situation is worse,” says Monoara. “Because of the flooding, there are not a lot of opportunities for work, especially for women in our village. My house is badly affected by this year’s flood, and many rice paddies got washed away.” Monoara moved to the capital city, Dhaka where she was connected to the NARI project, a World Bank initiative designed to provide training, transitional housing, counseling and job placement services for poor and vulnerable women. Since then, she has been able to support her family back in Kurigram and has gained financial independence. Monoara’s story highlights the importance of good development planning through programs like NARI, helping countries be better prepared for increased migration.

According to the report’s “pessimistic” scenario, South Asia is projected to have 40 million internal climate migrants by 2050, with Bangladesh contributing a third of that number. Right now, close to half of Bangladesh’s population depends on agriculture, so changes in water availability and crop productivity could drive major shifts in population. Bangladesh has already undertaken initiatives in the water, health, forestry, agriculture, and infrastructure sectors to mainstream climate adaptation into its national development plans. Several adaptation programs are underway, including a program to enhance food security in the northwest of the country and another to encourage labor migration from the northwest during the dry season.

Watch Wolde Danse's story

Wolde Danse, a 28-year-old from Ethiopia, is also turning adversity into a chance to change the course of his life. The eighth of 16 children, he left his father’s small farm in a drought-stricken part of his country and moved to the city of Hawassa in search of new opportunities: “In the planting season, it wouldn’t rain, but when we didn’t want it, it would rain. This created drought, and because of this, I didn’t want to suffer anymore.” After some initial struggles, Wolde enrolled in Ethiopia’s extensive urban safety net program, and now he receives a small salary for supervising street cleaners. As part of the program, Wolde can attend Hawassa’s university without paying tuition, and he’s planning to finish his studies to benefit his country and his family.

Without concrete climate and development action, Sub-Saharan Africa could have 86 million internal climate migrants by 2050, with Ethiopia one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change in Africa, due to its reliance on rain-fed agriculture. Ethiopia’s population is likely to grow by 60-85 percent by 2050, placing additional pressure on the country’s natural resources and institutions. Ethiopia is taking steps to diversify its economy and prepare for increased internal migration.

Sometimes, however, migration is not the answer.

Watch Javier Martinez's story

Some communities are finding ways to deal with climate change that don’t require migration. Javier Martinez, 26, and his brother have chosen to stay in their community in Oaxaca, Mexico and expand their carpentry business. They have been able to do so thanks to a sustainable forestry program that has helped to attract investors and enabled the community to adapt to a changing climate while building economic opportunities. Javier explains: “At the forest level there is employment, in businesses there is employment, so there is not a strong need to go away because in the community there is a wide range of opportunities.” Efforts like these around the world to build more sustainable forestry programs are paying climate dividends globally and supporting economies like Javier’s locally.

According to the report’s worst-case scenario, Latin America is projected to have 17 million internal climate migrants by 2050. Mexico is a large and diverse country in terms of physical geography, climate, biodiversity, demographic and social composition, economic development, and culture. Rain-fed cropland areas are likely to experience the greatest “out-migration”, mainly as a result of declining crop productivity. There will also be increases in average and extreme temperatures, especially in low-lying (and therefore hotter) regions, such as coastal Mexico and especially the Yucatan. However, as an upper-middle-income country with a diversified and expanding economy, a predominantly urban population, and a large youth population entering the labor force, Mexico has the potential to adapt to climate change. Still, pockets of poverty will persist, given that climate-sensitive smallholders, self-employed farmers and independent farmers tend to have higher than average poverty rates.

Taking action

Monoara, Wolde and Javier’s stories tell us that, while internal climate migration is a growing reality in many countries, it doesn’t have to be a crisis. With improved policies, countries have the chance to reduce the number of people forced to move due to climate change by as much as 80 percent by 2050.

The report finds that countries can take action in three main areas:

1. Cut greenhouse gases now

1. Cut greenhouse gases nowStrong global climate action is needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting future temperature increase to less than 2°C by the end of this century. However, even at this level of warming, countries will be locked into a certain level of internal climate migration. Still higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions could lead to the severe disruption of livelihoods and ecosystems, further exacerbating the conditions for increased climate migration.

2. Embed climate migration in development planning

2. Embed climate migration in development planningThere is an urgent need for countries to integrate climate migration into national development plans. Most regions have laws, policies, and strategies that are poorly equipped to deal with people moving from areas of increasing climate risk into areas that may already be heavily populated. To secure resilience and development prospects for everyone affected, action is needed at every phase of migration (before, during and after moving).

3. Invest now to improve data on the scale and scope of local climate migration

3. Invest now to improve data on the scale and scope of local climate migrationMore investment is needed to better understand and contextualize the scale, nature, and magnitude of climate change-induced migration. Evidence-based research, complemented by country-level modeling, is vital. In support of this, new data sources, including from satellite imagery and mobile phones, combined with advances in climate information, can help countries improve the quality of information about likely internal migration.

This report, which focuses on three regions—Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America that together represent 55 percent of the developing world’s population—finds that climate change will push tens of millions of people to migrate within their countries by 2050. It projects that without concrete climate and development action, just over 143 million people—or around 2.8 percent of the population of these three regions—could be forced to move within their own countries to escape the slow-onset impacts of climate change.