Quality research on climate change is critical as we work together to devise solutions for a sustainable future. However, when it comes to ensuring equity, diversity, and representation in climate research, the scientific community has a reputation for falling short. Why is this, one might ask, especially considering the heightened demand for a breakdown of systemic barriers in STEM fields? It turns out parachute science is often to blame. Parachute science is a term that describes the prioritization of research and expertise by privileged professionals over equally qualified, yet significantly more marginalized, women, BIPOC, and frontline researchers from the Global South.

Over the years, excellence in science and technology has become synonymous with significant funding, infrastructure and economic development. This is in part due to Western academic communities instilling the notion that their experts are the only true arbiters of discovery. Such posturing has served to downplay the expertise and findings of scientists in lower-income areas across Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. As Brazilian botanist Alexandre Antonelli explains, “For hundreds of years, rich countries in the North have exploited natural resources and human knowledge in the South.” This problem is perpetuated by the abundance of capital and materials at the disposal of scientists in the Global North, which dwarfs the resources available to their Southern counterparts. But why should developed nations be the only ones who have a say in the future of our planet? Surely working together and sharing resources is the best approach—so where is the collaboration?

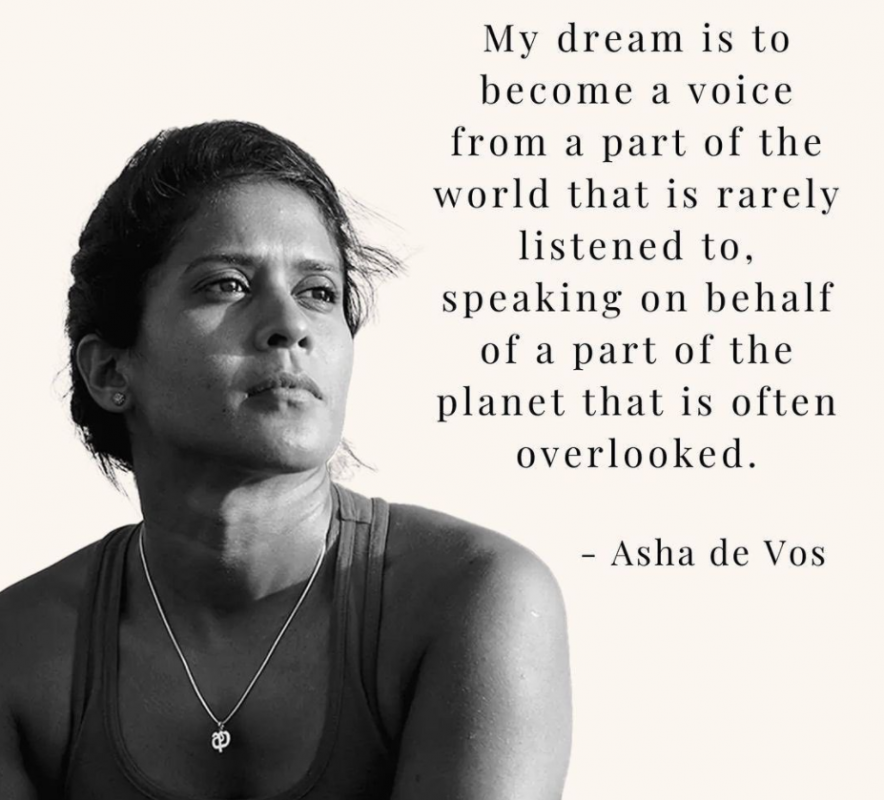

Sri Lankan whale researcher Asha de Vos has spoken out against the systemic problems of parachute science.

At the heart of the issue is the paradigm of parachute science, wherein researchers, typically from the developed world, carry out field studies in lower-income countries but travel back to their home country to complete the work. This is typically done without any further investment, communication or engagement with local experts from the origin country. As a result, local scientists are often subordinated to field work rather than analytical research or project leadership. For example, in 2003, when marine biologist Asha de Vos made a significant discovery about whale feeding patterns in her home country of Sri Lanka, she reached out to whale experts around the world for help kick-starting her research. But, as Scientific American reveals, the response she received was insulting to say the least: “This sounds like an exciting discovery. Please apply for a research permit so we can bring our teams out to study it.” Asha was confronted with the reality that these experts didn’t want to collaborate or join her on this project but rather take over and even sideline her capabilities to mere logistical legwork. It’s equally telling that, per a study recently published in Taylor & Francis Online, institutions in Europe and North America received 78% of all funding for climate research regarding Africa from 1990 to 2020, while Africa itself received a paltry 14.5%.

This parachute tactic not only undermines local conservation efforts but is also logistically impractical. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted hundreds of ongoing research studies now forced to navigate gaping holes in their data sets. Working anywhere other than one’s own home country is a privilege, not a right, and yet developed nations continue to promote dependence on their external expertise rather than empowering local authorities whose knowledge can strengthen the research in vital ways.

So how do we push past this self-serving and neo-colonial approach to scientific research? I’d argue it’s through a holistic emphasis on intersectionality–an emphasis taken to heart by AI-enabled carbon sequestration startup Albo Climate, which is pioneering ways to collaborate and verify the work of local stewards already effectively managing nature-based solutions to climate change. In recent years, I’ve been working with Albo on what just might be the key to healthy partnerships in developing communities: prioritizing the empowerment of local leaders through transparency, trust and respect before venturing ahead with mutual knowledge exchange. As someone who grew up in Africa and witnessed first-hand the inequity, resource disparity and blatant lack of respect towards the region, this work is very personal to me.

Author Sharona Shnayder (second from right) and her Albo Climate colleagues.

The solution to parachute science isn’t pushing external researchers out of the Global South entirely, but rather actively platforming and using methodical capacity building to empower local experts in underdeveloped regions who are all too often sidelined in their own countries. Education also has a key role to play: by supporting campaigns to bring climate change into the curricula of schools in the Global South, we can motivate a new generation of climate scientists to take the reins in their home countries and produce invaluable homegrown research to contribute to the canon.

The simplest way to help now is to keep the discourse around parachute science alive by starting conversations in person and online. If we’re persistent enough, the failings of the existing system will be laid bare, and a new paradigm will rise to take its place. Steps in the right direction are as simple as alliance, asking questions, sharing technology and literature, giving credit where it's due, learning the regulatory landscape, and being transparent in operations. It is through the collaborative approaches of companies like Albo Climate, coupled with empowering educational initiatives, that we will be able to open the doors for a fresh generation of climate researchers who will bring critical representation to the global stage. If we do not work inclusively and acknowledge privilege where it lies, then we will continue to fail, and failure is not an option when it comes to the climate crisis. It is time we collectively close the door on parachute science and open the conversation to develop a new, symbiotic research paradigm. It is the only way to get things done.

Sharona Shnayder is a Nigerian-Israeli Environmental Activist and Marketing & Brand Manager at Albo Climate She is the Founder of the global movement Tuesdays for Trash and Chairwoman of the nonprofit Our Streets PDX. She has spent the last three years advocating for climate justice and using her writing to highlight the waste management crisis while demanding intersectionality within the climate movement.

Banner image (reversed from original) courtesy of ThisIsEngineering, Pexels.